Tetris, and Getting my Girlfriend Addicted to Tetris

Searching for the word Tetris on Google will result in 92,900,000 results. Searching for PacMan produced 91,200,000 results. That’s a difference of 1,700,000 search results. I didn’t compare these results against Bing, because I have standards, and a soul. These search results will be important later in this essay.

On a related note, I got my girlfriend addicted to Tetris.

Here’s how it happened: I played a lot of Tetris.

That's it. That’s how easy it was.

I don’t mean to suggest by that sentence that my girlfriend is stupid or easily swayed or manipulated. Anything but. I say this in full honesty in her favor, the woman could probably convince a freight-train to turn around and move in a different direction if she spotted a cute bug on the track and didn’t want it to get smooshed. That’s the level of her conviction and personal integrity.

What I hoped to convey in that sentence, as well as in the rest of this essay, is that Tetris is a videogame that has an infectious quality that would make the Bubonic plague and Covid-19 blush, and it’s due in no small amount to the fact that the game is an abstract masterstroke that scratches a deeply psychological itch.

It’s also, and this is important, really fun to play.

Tetris is an abstract, action, puzzle videogame originally created by Alexi Pajitnov a Russian programmer who formerly worked for the Soviet Academy of Sciences as a speech recognition researcher. There is no plot or setting to Tetris. The game opens in an empty rectangular space and geometric forms composed of a series of squares called tetrominoes begin to fall from the top of the screen. Players can, using buttons on gamepads or keyboards, turn these pieces at 90 degree angles in order to try and fill horizontal rows within empty space. The goal is to line these pieces together in complete horizontal lines. Once a line has been constructed it will disappear and the player will be rewarded points, and the more rows that are completed at once will increase the points earned. The challenge of the game is that the player has no control which tetrominoes will appear as they play, meaning that particular pieces may not be advantageous for completing a row and the player has to decide where to move this piece so as not to create any gaps. Likewise as the game progresses the speed at which the tetrominoes drop increases giving the player less time to turn them the right way before they land and another one appears.

The most important aspect of Tetris however is that a game does not stop until the tetrominoes are stacked all the way to the top. This is to say, Tetris doesn’t stop until the player loses.

The implication of this becomes obvious: there is no way to “win” at Tetris.

Which then begs the question, why would anyone play Tetris? And why is it still being played today?

I suspect one reason is because Tetris is a game, in the most pure and abstract sense.

Take the plot of Final Fantasy VII, one of the most popular video games of all time. The plot of the game is that Cloud Strife, an Ex-Soldier is working as a mercenary and becomes tangled in the plot of the eco-terrorist organization Avalanche who is blowing up the power generators of the Shinra corporation. Avalanche is trying to stop Shinra from draining all of the Mako (life essence) from the planet and creating an environmental apocalypse. During the second mission the group is attacked and separated and Cloud meets a young woman named Aeris (in the original) who is, we later learn, one of the last of an ancient race of organisms that inhabited the planet centuries ago and is being hunted by Shinra who wish to study her. During a rescue operation, the group encounters a former soldier known as Sephitorth who is a bio-engineered super-soldier who has gone insane after discovering the truth of his origin and is working to have a meteor collide into the planet.

Tetris…is about moving blocks of squares together to form lines.

I’m using this context to note that Final Fantasy VII is a crazy, bonkers-brilliant, fantasy, cyberpunk adventure and an incredibly brilliant and emotional story. It’s also a reminder that it’s difficult to just hop into the game while I’m riding a bus to work or waiting in line at the DMV.

Tetris as a game is not devoid of emotional potential, but it provides a simpler interface that fosters abstract thought and play. When I’m playing Tetris my concern is not the emotional weight of the choices I’m making, or the nuances of role-play dynamics; I’m simply trying to move tiles into proper order to avoid gaps. There is an ease of access to Tetris that is at the core of its appeal to players. Like a game of checkers or that Cracker Barrel Peg Game(Google it) Tetris can start and stop without any emotional investment.

And, truthfully, I can’t say I’ve ever been emotionally invested in Tetris.

I have been intellectually obsessed with it.

And clearly I haven’t been the only one.

Researching for this essay I found an article published on WIRED magazine titled “This is your Brain on Tetris” by Jeffrey Goldsmith. Published 1 May 1994, the article explored the neurochemical process that takes place in the human brain while playing a game like Tetris. Goldsmith writes:

In first-time users, Tetris significantly raises cerebral glucose metabolic rates (GMRs), meaning brain energy consumption soars. Yet, after four to eight weeks of daily doses, GMRs sink to normal, while performance increases seven-fold, on average. Tetris trains your brain to stop using inefficient gray matter, perhaps a key cognitive strategy for learning. In fact, the lowest final GMRs are found in the best players' brains, the ones most efficient at dealing with Tetris's Daedalian geometry.

The elevated GMR "high" is why you get wired after hours of play. Your old dog of a brain learns the Tetris trick by munching cerebral glucose. Neural hoop-jumping seems to be streamlined until performance peaks, and then your old dog stops craving Milkbones.

The Tetris effect is a biochemical, reductionistic metaphor, if you will, for curiosity, invention, the creative urge. To fit shapes together is to organize, to build, to make deals, to fix, to understand, to fold sheets. All of our mental activities are analogous, each as potentially addictive as the next.

How a poet's mind struggles to compose a phrase is equivalent to a how an engineer frets - we hope - over a new concept in bridge suspension, or how a neat freak invents infinite corners to dust, or how anyone gazes into perpetual motions in liquid crystal.

Several years after this article was published the videogame developer and critic Tim Rogers offered his own unique take on the intellectual impact of the game on his website Action Button.net. Published on the 5 November 2009, the article simply titled “Tetris” tries to offer explanations and observations about the appeal of Tetris as a videogame and how it lodges itself into the depths of a player’s brain. Near the end of the article Roger’s writes,

What captivated the greater portion of the human race when it came to Tetris was the fact that simply playing it, staring down death between those cold walls, maybe (definitely) dropping pieces in time to the bouncy Russian-like music if you were playing it on Gameboy, was an experience in learning something about yourself. As you made mistakes and faced them, session and session again, you grew more and more intimate with some kind of emerging pseudo-consciousness. Riding a train, relaxing on a cruise ship, waiting for an airplane to take off, or killing time in the den, Tetris can remind us of where we are, and what vehicle we may be riding or about to ride. It’s the closest the average human will get to feeling the way Garry Kasparov felt when declined a rematch against Deep Blue.

It’s a pretty excellent feeling, for what it’s worth. And it certainly deserves a place on our list of the best games of all-time.

I’ll be the honest, the first intellectual impression or lesson I’ve ever acquired from playing an hour or more of Tetris has typically been an appreciation that I’m in my 30s. I’m no longer a child which means I can basically do whatever I want with my free time and money, and if I want to spend it on something like an hour of videogames and a pizza then no-one can stop me. It’s a gas and I can’t imagine ever wanting to be a kid again.

But, after this first thought, I do admit that Tetris has been an intellectual obsession and not just because of the cool math that makes up the process of playing the game.

Starting a game of Tetris and then playing even just for five minutes I recognise a familiar flow state that I’ve encountered while playing videogames throughout my existence. Moving the tetrominoes across the empty space of the board has a lovely joy of motion, but the satisfaction of placing the tile far supercedes anything else in the game. The gaps between squares become the centerpoint of my attention and without even having to think I can perceive my brain formulating the structure of the bricks in my mind. Tetris becomes a building simulator.

For context. when I play games like StrongHold Crusader, Pharaoh, Rise of Nations, or Sims Ant (I’ll get to that one in the future I promise) there’s a comparable flow state. I begin to perceive the map as a series of squares. Buildings, roads, and structures become tetrominoes. However, at some point I recognize the divide because the latter mentioned games are about establishing stationary objects. The towers, granaries, barracks, roads, and statues I build in a traditional simulator game will not disappear unless I actively select them for destruction.

Tetris pushes me to continually check those spaces because at some point the structures, or more accurately lines, will disappear and the process will begin again.

Cover image provide by The Cover Project website.

The psychological and biochemical effects of playing Tetris aside, I remain stuck on the question as to why I play and have played so much of the game. Looking at most of the videogames I spend my time and energy on a majority of them are action based, meaning that I’m controlling some avatar and moving through a fictional reality because I’m either following a story, engaging in some sort of action-adventure, or because I’m solving puzzles in 3D or 2D space. Whether it’s games like Portal 2, Super Mario Bros 3, Alice: Madness Returns, Fallout 4, Red Dead Redemption 2, Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom, DOOM, or even flipping Capybara Spa all of these videogames involve moving human, humanoid, or animal sprites for the purpose of arriving at a goal. The joys of these games are about working towards that goal, and even when the game is “over” there’s a satisfaction in knowing I can start again and enjoy that process.

With Tetris, there is a tremendous amount of satisfaction in the process, but unlike the previous games that engage me through a narrative structure Tetris is purely abstract. It’s a puzzle videogame about structuring reality until it disappears.

Tetris could be considered a “death simulator” in some respects, but that title doesn’t accurately fit the mental perception I have of the game.

In fact if I’m being honest, a more accurate descriptor would be “life simulator.”

Hear me out.

The act of participating in reality (whatever the flip that actually is) involves navigating the structures and energies around me. I wake up in my bed (which is a rectangle) and get up. Depending on the day I either make coffee and start to write or draw for several hours, or else I get dressed in my professional ensemble and go to the public library where I work. This job involves turning on a computer, answering emails for coworkers, helping patrons finds books and giving them directions to the computer lab, I work on research requests in the Local History room, I process and index obituaries published in the local newspaper, I listen to patrons who are annoyed or angry or happy or excited about the events of their life, I make copies of informative pamphlets for using Library resources, I help kids find Minecraft books (because Minecraft is awesome), I notarize documents, and at the end of the day I clock out, come home, and try to write or draw for a few hours before going to bed.

If I don’t do that I play videogames or read a book(often about videogames or histories about gay people).

Looking at this list my brain performs the exercise of arranging these tasks and actions into abstract shapes that may or may not resemble tetrominoes. Certain tasks possess philosophical shapes like straight lines, a bent “s,” or even a square. As these tasks fall down I try my best to recognise them for what they are and then arrange them as best I can within the rectangle of my day. I try to make sure that these tasks have order, but inevitably the same recurring shape disrupts the flow and before I realize it the shapes have created gaps that I have to address, or at least try to. But anyone who has lived in reality knows that tasks and actions don’t stop. Because there’s also activities like grocery shopping, getting the car fixed, calling your mother(because she worries about you), doing laundry, taking pets to the vet, meeting that person you met at the grocery store to go miniature golfing, washing dishes, and calling the credit card company back because you know you didn’t buy $500 worth of Hummus at a Trader Joes in Sheboygan, Wisconsin.

Fun fact, there ain’t even a Trader Joes IN Sheboygan, Wisconsin.

I Googled it!

No matter how well I try to navigate these tasks there will be gaps that will form. As much as I would like to tell myself I will have time to work back to those tasks, anyone who has been alive for more than 26 years know that time does not slow down. In fact the precious seconds that began this game will begin to seem like milliseconds as more and more actions begin to stack together.

I was eight years old playing Super Mario All Stars on my parents’ Super Nintendo Entertainment System, and before I realized what happened, I was 35 and playing Tetris on my Nintendo Switch.

And there’s still more tasks, actions, and tetrominoes to organize.

I hope this poorly executed metaphor at least gives some insight into how Tetris scratches the psychological itch it does. Like I noted at the beginning of this essay, Tetris doesn’t stop, it doesn’t end, there is no way to “beat” the game. Players can only play and experience Tetris, achieving small victories over time. Even the most hardcore player who can play Tetris for hours is still never going to be able to beat the game because there is no way to beat Tetris.

Tetris is like experiencing life and reality, and there is no possible way to complete that experience.

Except, maybe to die.

But, while we’re still living, I’d like to go back briefly to Tim Rogers’s essay about Tetris, because the start of his essay offers another important insight to the game. Rogers writes:

Tetris has been released in probably more versions than ice cream has ever had flavors. We are autistic, though not nearly autistic enough to list every version of Tetris that has ever been made. For the purpose of this review, we’re going to “imagine” a certain variety of Tetris. We put “imagine” in quotation marks, like that, because for all we know, this version actually does exist somewhere. Come to think of it, it would be terrible and presumptuous to think that it doesn’t.

Tetris is a game where you always lose. In Tetris, the closest you get to feeling like you’ve won anything at all is when you narrowly prevent yourself from losing. Tetris is a grim exercise in death education. It is an unchanging, unflinching, unfeeling opponent.

A greater percentage of the world’s population has played Tetris than has played any other game in the history of games. We can’t prove this. We can, however, feel it. Let’s put it into easy words: Tetris is the most popular game that has ever existed.

Apart from the soul-crushing realization that I will never in my life write a sentence as perfect as the first line of his essay, I find Rogers’ observation about Tetris beautiful. It’s a wonderfully human observation about a software program that, literally decades after it was first created, still manages to inspire dedication, addiction, psychological turmoil, and most importantly comfort in players who enjoy the game.

I mean it literally when I write that Tetris is iconic.

It’s iconic the way Pac-Man is iconic. At which point my opening sentence has hopefully become relevant.

The success of both of these games, both of which are about moving icons within the confines of a rectangle, are extraordinarily popular video games that are still being played because they appeal to something deeply relevant to the human mind and soul.

Though, as my search results noted, Tetris is more popular.

Moving Pac-Man through the maze and eating pellets and fruits revolutionized the videogame medium in no small part because it appealed to everyone, and not just a portion of the population. Girls…, I meant girls. Girls loved Pac-Man as much as boys did. Toru Iwaani designed Pac-Man in such a way that it didn’t matter who played the game, anyone could enjoy it and identify in the characters and visuals something about themselves. Alexi Pajitnov, several years later, approached his own game with a similar mindset.

Humans played, and humans continue to play Tetris because of its universal appeal. Tetrominoes trigger something in my own mind that I recognize is far older than myself; it’s the very concept of play and creativity.

Life is many things, but one of the defining qualities of humanity is imagination and the way it allows the species to engage with reality beyond the basic needs of survival and reproduction. In this space between the biological extremes there has been play, and the desire to play. Tetris fits perfectly between those two states, like the piece we’ve needed desperately for the last few minutes to clear the line allowing us to develop more complicated and nuanced varieties of play.

I don’t want this essay to end in abstract philosophy because there’s already so much of that in the conversations that surround Tetris(especially in this essay). Instead I’ll end with a personal anecdote which I think goes a long way to demonstrating Tetris’s impact.

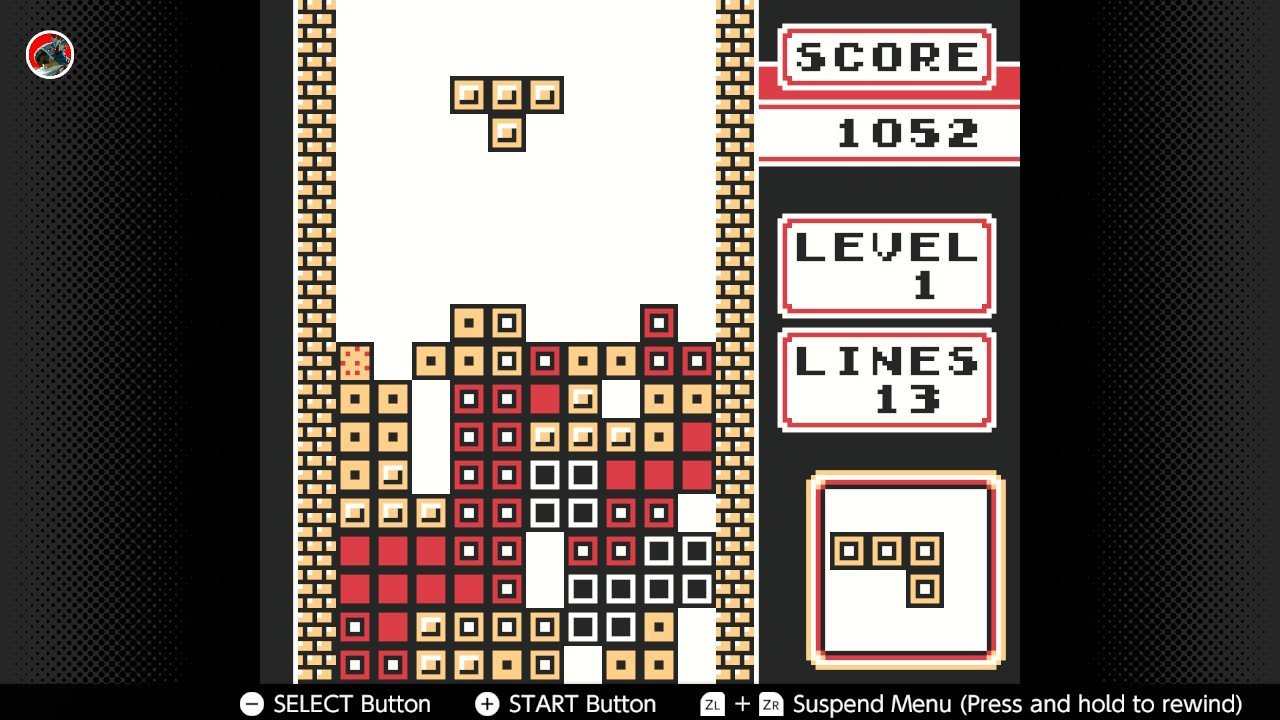

One night, several months before I wrote this sentence, I was sitting on the couch playing Tetris on my Nintendo Switch while my girlfriend sat next to me scrolling through Facebook. I was having a rough match, there were several gaps already, and I moved the “T” shaped tetromino into the line I was making. As soon as the blocks had landed I heard a small “tsk tsk” followed by my lovely, beautiful, and intelligent girlfriend who said, “You did that wrong.” I could only respond, “What do you mean, I did that wrong?” She responded with, “You should have shifted it sideways and placed it along the left hand side, it would have given you a better position to start stacking the blocks and set up four rows.”

The woman who had never even heard of Tetris before she started dating me had, in the space of just a few months, become a seasoned player and I was left bumfuzzled at her progress, and frustrated because, much as it pains me to admit, she was right(she always is) and I lost that game a few seconds later.

Joshua “Jammer” Smith

9.30.2024

Like what you’re reading? Buy me a coffee & support my Patreon. Please and thank you.