Postal by Brock Wilbur & Nathan Rabin: Book Review

I would never have played the videogame Postal.

Let me explain.

Because I was the sort of weenie who thought I would have been psychologically scarred if I played Diablo II for PC, I can’t even imagine what my teenage self would have thought about Postal. Nevermind the fact that I would stare at the covers of horror VHS tapes at Hastings whenever I went out with my parents and study every revolting detail of every Hellraiser and Leprechaun cover. Most of the Real-time-Strategy(RTS) videogames I played had animations of characters being shot with arrows or having their skull crushed in by a mace. I should also mention the fact that I loved the Lord of the Rings films which included multiple fight sequences of Orcs (and Uruk-Hai(thank you Gimli)) being shot with arrows,stabbed, beheaded, having their necks broken, etc. I also played Assassin’s Creed II and when I wasn’t stabbing Templars in the back of the head, I would spend my time beating guards to death with clubs and even a broomstick. I played Freedom Fighters which had me shooting and killing Russian Soldiers; one cheat code even turned my bullets into a Nail Gun which would literally nail bodies to the walls. And, of course, I played a lot of Call of Duty: Modern Warfare games which had me perforate endless populations of digital enemy non-playable-characters(npcs) with shotguns, assault rifles, pistols, and grenades.

This is to clarify, violence wasn’t something I was unaware of. But I was consuming media which had a superficial representation of violence.

Postal’s violence isn’t realistic, but as Brock Wilbur and Nathan Rabin point out in their book Postal, it isn’t terribly pleasant or enjoyable to experience.

As of this writing, I’ve written several reviews of the various titles in the Boss Fight Books series because, as I’ve noted in every one of those essays before this, I absolutely love these books because of what they’re doing for videogame discourse. Each book is uniquely crafted, well written, carefully researched, and manages to leave the reader with an individual take on how videogames shaped the writer. Rather than just wax philosophic about how videogames should be taken seriously as a medium, the Boss Fight Books series already approaches each game with that perspective in mind. The ethos is, simply put: videogames are art, and here’s one that’s interesting.

That’s probably why Postal is such a difficult book for me to write about because, by the end of it, I wasn’t sure if Postal (the videogame) was actually that interesting, or even worth playing. I note though that I did go to Steam, bought it, downloaded it, and tried to play it. I try to play all of the games of Boss Fight Books once I’ve read the book, or while I’m reading the book.

Spoiler alert. Postal isn’t that fun to play.

Actually, Postal sucks.

And I know I’m not alone because Wilbur says as much himself. He writes in one passage about the actual experience of playing the game:

There is no sense of spectacle or performance in how you mow down your neighbors and the local law-enforcement. The only sounds are the guns, and then the tormented wails of your victims as they twitch on the ground bleeding out. Very quickly, this chorus of death rattles starts to loop and layer to such an extreme that borders on a dance remix of tragedy.

I always expected Postal to be more of a lighthearted rampage. This is painful. And bleak. And not particularly fun. (18).

Postal is an isometric, top-down, action, shooter-game released in 1995 primarily for Macintosh Personal-Computers(PCs). The player controls the character known simply as The Postal Dude and the goal of each level is simple: kill everyone. This isn’t anything terribly revolutionary to videogame narrative design, and there’s plenty of games I enjoy that use this narrative. The goal of DOOM is to kill all the demons, the goal of Gears of War is to kill all the Locust Horde, the goal of Spartan: Total Warrior is to kill all the Romans, and the goal of any Kirby game is to kill all the Waddle-Dees…

All, of, them.

Postal, however, was and is unique because the game sets the goal of killing all the npcs on the field, and these npcs are normal people. The Postal Dude is armed with a machine gun, a shotgun, grenades, molotov cocktails, bombs, etc. and has to kill his neighbors, town-folk, police officers, and then eventually members of the military. The point is the people he’s killing are no real threat because they haven’t done anything to him. And as for why he’s killing them, there isn’t an explanation.

Well, there kind of is. Through end-game cutscenes where Postal Dude tries to kill the children of an elementary school we’re eventually shown a scene where it’s heavily implied that he is now locked away in a mental institution, and that his whole psychotic rampage was merely the end result of his psychosis. This ending was changed when the game was rereleased as Postal Redux, but the psychiatric ward scene remains the same.

Postal Dude is going postal (get it?) and killing everyone because he can, and because he suffers mental health issues.

And this is where things become difficult.

Postal was released four years prior to the Columbine high-school Massacre, and the shooters in question were fans of Postal and other controversial FPS videogames, which did not go unnoticed by the news media and law-enforcement. Bodies were barely cold before Postal, and other first person shooters like Duke Nukem and DOOM were decried as the primary culprit for the massacre. Postal unfortunately lends itself well to this criticism because unlike the previously mentioned games, there wasn’t an ironic distance, or tongue in cheek tone to the game that helped remind the player that they were playing a videogame and that this was supposed to be entertainment.

Put another way, DOOM tries to be funny, Postal just wants to shock.

Wilbur manages in his section of the book to continually try to understand Postal, not simply as a videogame that created a response from critics, but as he notes in one passage that tends to be difficult. He writes:

Despite the midling reviews, the game was kept afloat in the cultural consciousness not just by its blatant shock value, but by the extreme reactions it provoked from perennially offended news outlets, and opportunistic politicians. Even years later, it remains a topic of note in the history of violent video games. (14).

I’m writing this review in the year 2024, and the essay itself will be published on my website sometime later in the same year. It’s important to note these details because as I’m writing this sentence there is already a Wikipedia article for Mass Shootings in the United States for the year 2024. The website gunviolencearchive.org, which tracks instances of mass shootings in the United States, and even has an interactive map to show where they are happening, documented at least 49 shootings in the first 45 days of the year. I wrote this sentence on 19 February 2024, and by the time this article is published there will be more.

Wilbur and Rabin’s book was published in the year 2020. For the record, there were 614 Mass Shootings in the United States according to the Wikipedia article for Mass Shootings in the year 2020.

Excuse me while I go smoke a cigarette.

I do need to clarify that Wilbur and Rabin’s book is not about mass violence, or at least not directly about it. Like all of its precursors in the Boss Fight Books series, Postal is about the videogame Postal, and trying to understand it in relation to the culture, history, politics, economics, and technology that spawned it. Though here I note, half of the book isn’t even about the videogame itself.

Nathan Rabin’s portion of the book is about the film Postal which was directed by Uwe Boll. And I will admit in the interest of honesty that these sections were not my favorite part of the book, and not because Rabin isn’t a good writer. He is. Rabin’s section is an interesting addition to Wilbur’s because both try to understand the main figures behind Postal. Wilbur’s book contains numerous selections from his interview with lead game designer Vince Desi, and Rabin’s book includes plenty of interviews with Uwe Boll. Both of these sections are great for the way they are executed, and fascinating to read because they tend to mirror each other. That is to say Desi and Boll come across as mirrored versions of each other. Desi and Boll are both creators whose work has been heavily criticized, both men tend to act defensive and often lash out at the industries they work in, both men are considered by their contemporaries and critics as the worst examples of their profession, and both men seem rather unhappy.

But, even while observing these details, Postal is still about the videogame Postal. And Postal is a pretty violent videogame.

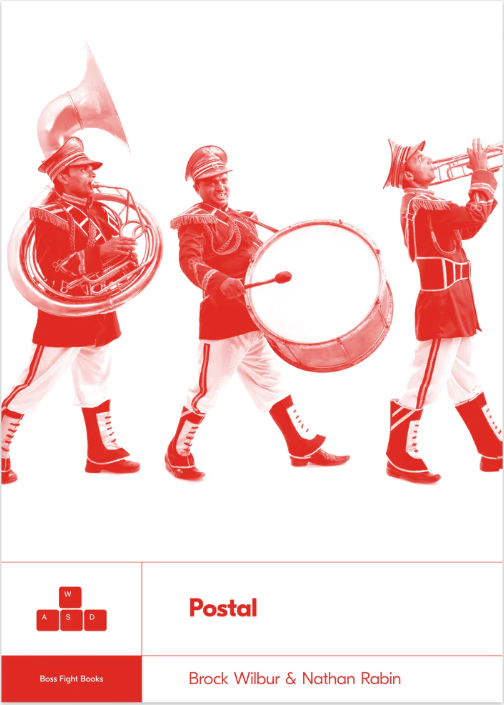

In a later portion of the book Wilbur describes what is still the most famous, and arguably the most entertaining moment of the game. This sequence involves the player setting fire to a marching band. Wilbur does a great job narrating this sequence and communicating how fun this part is, and I even laughed while reading it. But once this moment is done Wilbur is able to reveal how this one moment betrays the quality of the rest of the game when he writes:

With no further moments of chaotic blood- joy to build upon after the marching band, the biggest changes in game are simply background details and gags. The Air Force Base has a missile firing helicopter you have to bring down, even though it’s already on the ground. The aforementioned Ghetto level contains wig stores and payday loans, but also a desecrated Church, and even the offices for Running With Scissors–where protesters with picket signs wait for you to fire on them and prove their concerns about the dangers of video game violence to be correct.

But it’s not fun. None of it is. Every baddie, even on the easiest settings, is an absolute bullet sponge. Levels often trap a few characters in some far off corner, forcing you to hunt them down long after the massacre portion of your experience has concluded. Postal becomes, oddly enough, a simulation of work. If you were to replace all the bullets with mail and make this game about needing to deliver 10 pieces of mail to 100 random people in every map this would be an accurate game about working for the Postal Service. (50-51).

Violence in video games tends to perpetuate because, despite the misguided optimism expressed by a handful of loud voices that decry it, human beings can derive entertainment from violence in artificial environments…when it’s done right. This is one of the reasons slasher-horror films can create a rabid fan-base and spawn sequel after sequel long after the original horror of the first film has faded. And, as I noted before, a videogame like DOOM speaks for itself since one of the most entertaining moments is when the Slayer acquires a chainsaw and begins shoving it into the torsos of every Imp unfortunate enough to not run away fast enough.

But, again, DOOM is fun damn it.

^Brock Wilbur being interviewed by Boss Fight Books Editor Gabe Durham

By the end of Postal (the book, just so we’re clear) Wilbur and Rabin had managed to chronicle the development, reception, and legacy of the game and its media tie-ins, and much as it pains me to admit it, I didn’t like the end of it.

I want to be clear, Postal is a great book, and my reader should read it.

What I’m simply trying to communicate, unsuccessfully, is that Wilbur and Rabin manage to explain why a game as unfun and unlikeable as Postal continues to have meaning and relevance to society literally two decades after it was released. And the conclusion they arrive at is one that isn’t terribly uplifting or hopeful, but does ring painfully accurate. Wilbur writes near the end of the book:

So how does Postal relate to our broken world? Ultimately I think it’s more symptom than cause.

Postal is a game about encouraging the absolute worst instincts of your reptile brain, in the service of the immediate dopamine rush that animated violence might unlock. It’s a shooter among thousands unique at the time only for its nastiness–for how it does away with any semblance of heroics, though at this point other games have improved on that trope too. (151)

And a page later he sums it up beautifully as he writes:

Postal is not the failure. We are the failure. This artifact from the mid-90s tauntingly reminds us of our cowardice. Postal succeeds in replicating the near monotonous repetition of gun violence in our society to the point where it is impossible to summon a positive or negative reaction to the game itself. It just looks a lot like the news. (153.)

There are so many books and essays about videogames, and a great amount of this content is dedicated to extolling their virtue or else damning them as a malicious vice. Apologists for the medium have regularly had to defend videogames against interest groups whose ultimate goal is typically to distract us from regular tragedy that is due, always, to individuals with access to firearms and undiagnosed mental health disorders. A book like Postal is a unique book then because rather taking one side over the other, it observes the game for what it is: a crass work of schlock that’s sole purpose was to shock and offend.

Any medium has its share of works that over time are remembered for their value and contributions to the form. Postal is a unique videogame because it manages to capture an energy that didn’t contribute much to the medium, but somehow managed to maintain a cultural relevance. After 20 years (really 19) a videogame about shooting unarmed civilians with shotguns, assault rifles, grenades, and handguns is still relevant. Wilbur and Rabin's book manages to show their reader how such ugly simulated realities eventually just became reality.

If the philosophy of videogame design is crafting new worlds for players that they’ve never seen before, then the makers of Postal achieved a kind of philosophical victory because their game did succeed. They made a world no one should have wanted to play, and now they don’t even have to play it.

Joshua “Jammer” Smith

6.24.2024

You can grab a copy of Postal by Brock Wilbur and Nathan Rabin by following the Link below:

Postal by Brock Wilbur & Nathan Rabin – Boss Fight Books

Also check out this great video of Brock Wilbur being interviewed by Boss Fight Books’s editor Gabe Durham:

Gabe Durham Interviews Brock Wilbur about his Postal book for Boss Fight Books - YouTube

Like what you’re reading? Buy me a coffee & support my Patreon. Please and thank you.