193 Imps: Doom

I don’t want to talk to an Imp, I only want to punch or shoot them.

Let me explain.

Since their first appearance when DOOM was released in 1993, Imps have provided players of DOOM plenty of headaches. In fact the first real appearance of the non-playable-character(npc) was not even on a level playing field. Literally. When the player arrives in the “zig-zag room” of E1M1(Episode 1, Mission 1, aka The Bunker) there are possessed soldiers, “Shotgun jerks,” waiting on the floor level to kill the player, but then in the corner on a raised platform is an Imp (or Imps depending on which difficulty setting I have it set for). Given the fact that the first game doesn’t need aim adjustment it’s not too difficult to kill these enemies growling at me from on high, but Imps are unique for their long range attack: fireballs that grow in size as they approach the character.

I’m currently reading David Kushner’s book Masters of DOOM and he describes in one passage the reaction these fireballs had on players who first played the game when it was released:

Two hundred feet under Waxahachie, Texas, inside the U.S. Department of Energy’s Superconducting Super Collider Laboratory, Bob Mustaine flew back in his chair. The government man was terrified. He wasn’t the only one. Across the room, his colleagues also twitched and screamed. This had become a daily occurrence at lunchtime. In all their days studying particle physics at the country’s most ambitious research facility, they had never seen anything quite as shocking as the fireballs erupting on their computer screens. Nothing–not even the multibillion-dollar subatomic shower of colliding protons–blew them away like DOOM. (158-159).

Seeing these fireballs today doesn’t make me scream or jump back, mostly because I’ve played Doom Eternal, and I’ve also played a lot, and I mean a lot of classic Doom.

At the end of E1M1 I arrive at the last door, conveniently marked “EXIT” and when I open the door it springs out at me: another Imp. Its body is a light ochre-brown broken only by the white spike jutting from its arms and legs, and the bright red of its mouth which is open and roaring at me. A quick shotgun blast and the imp is ground into hamburger meat. This last attack from the Imp is not a great challenge, because it’s not a challenge at all, it’s a message. This isn’t over.

It’s clear from this last obstacle, I’m going to kill a lot of Imps in this game.

Opponent npcs in games vary in form and difficulty, not only in Doom, but across video games period. Goombas in Super Mario Bros, ninjas in Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, octoroks in Legend of Zelda, beetos in Shovel Knight, Skeletons in Diablo 2, or sixth graders in SouthPark, The Fractured But Whole are just some off of the top of my head. Each of these enemies provides the same general function to the player, namely, they are obstacles to movement.

In a game like Doom movement is everything, as I noted in a previous essay about E1M1. Imps, like any npc in the game, can become frustrating because they impede movement, and thus create the opportunity for the player to determine how they are going to continue to move forward.

Imps are also typically my first thought whenever I think about playing Doom, more so than any of the other demons I may encounter on my mission. And thinking about that I began to wonder how many Imps do I actually encounter?

Fortunately I was not the only person to consider this and the DOOM wiki page provided me with the data I needed.

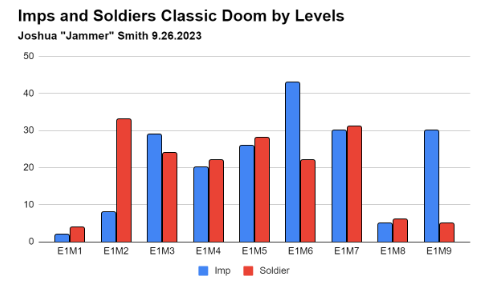

If I play Classic Doom on the level of “Hurt Me Plenty,” usually considered the “normal” difficulty setting of the game, and begin with E1M1: The Bunker, I will encounter 2 Imps during the total run. To put it in perspective I will also encounter 4 possessed soldiers. That’s a 2:4 ratio, which breaks down to 1:2, meaning for every Imp there is at least two soldiers. Once the level is done I move to E1M2: The Nuclear Plant. The total number of Imps in this level comes out to 8, with 33 soldiers. Moving to E1M3: The Toxin Refinery there 29 Imps and 24 Troopers. E1M4: Command Control has 20 Imps, 22 Soldiers. E1M5: Phobos Lab has 26 Imps and 28 Troopers. E1M6 Central Processing has 43 Imps and 22 Troopers. E1M7 Computer Station has 30 Imps and 31 Troopers. E1M8: Phobos Anomaly has 5 Imps and 6 troopers. And finally E1M9 Military Base has 30 Imps and 5 Troopers.

Taking all of these numbers together I made a small graph which I have included below:

I recognize that this chart is not perfect because it includes only Imps and solders/troopers/shotgun-jerks, and it only covers the “Hurt Me Plenty” setting, but I wanted some kind of visualization to show that, while the player in classic Doom is going to encounter a number of enemy NPCS which will inhibit movement and provide them challenges in terms of moving forward, the enemy that they will encounter, or likely encounter the most of is Imps.

There are, throughout the entirety of Episode 1: 193 Imps.

Those are 193 enemies that will scream, sneak-attack, and hurl fireballs at the players.

And because I want to make sure I’m not ignoring the obvious implications of the data, there are also 175 Soldiers. These npcs also represent an ever-present threat and obstacle and I do want to talk about them in another essay at some point.

Right now, for this essay, my concern is the Imps.

As a game DOOM has sometimes been criticized for its seeming simplicity. The player explores the various levels, fights demons, explores more regions, fights more demons, and reaches the exit. However, this criticism often reeks of an attitude of complexity for complexity’s sake. By today’s standards of Triple-A, open-world games that can take 180 hours or more to “complete,” DOOM would seem basic. However the “flavor” of the game, if I may borrow a term from videogame critic and designer Tim Rogers, speaks for itself. Doom is about exploring and shooting the way Pac-Man is about eating, the way Super Mario is about running and jumping, the way Street Fighter 2 is about fighting, the way Cubivore is about…well, I’ll get back to that last one. The point is games that possess only a few “flavors” may come across as deceptively simple, but playing Doom I never emerge from the experience as if I’ve been cheated of my time.

Exploring the Hanger, the Nuclear Plant, or the Phobos Zone and killing the Imps who have killed my fellow space marines is the point. Doom is interactive media and so Imps play an important function in that artistry of interactivity. The obstacles to completing the objective of running through and exploring the base is where the conflict arises and, therefore, the fun.

It’s fun killing Imps because it’s overcoming an obstacle. Specifically an obstacle that doesn’t want to talk to me, it just wants to kill me.

Minor npcs can become just as iconic to a videogame as the protagonist, and a perfect example of this are Goomba’s in the original Super Mario Bros. When playing the first level, World 1-1 I will encounter exactly 16 Goombas and 1 Koopa Troopa. And if you think I didn’t make a chart for that you clearly don’t know me at all.

While the larger game narrative of Super Mario is rescuing Princess Peach from Bowser, the reality of level-by-level experience is fighting Goombas, Green Koopa Troopa’s, and Piranha Plants to name just a few. Looking at DOOM, the player will eventually fight the Arachnatron responsible for the invasion of the Mars colony, but the actual experience of playing DOOM will largely be fighting and killing Imp after Imp.

These numbers matter, not just because I went to the trouble of rigging up a chart (I did that for fun), but because they shape the reality of the game.

I will encounter Pinky-Demons, Cacodemons, Barons of Hell, CyberDemons, and even the dreaded Arachnatron on my journey to rid the Mars colony of the infestation of hell-spawn, but along the way to killing those larger and more intimidating foes, I’m going to kill a lot, and I mean, a lot of Imps. Considering Imps as a game design element as well as a rhetorical structure, the design of Doom is about establishing impediments to movement and allowing players the chance to learn how to better navigate those obstacles. There is of course the option to simply run past all 193 Imps, and not waste a single shotgun shell. And there almost assuredly is a player out there who follows that path.

For myself, I choose to rip and tear until it is done.

Imps are just one example out of thousands of basic-level npcs that are designed to challenge the player’s ability to move through a simulated environment. Their numbers alone are a testament to how such characters operate in video games. Unlike others however Imps have managed to endure, even up through the most recent iteration of the DOOM series, DOOM Eternal.

I guess I’ll end noting that I wish I could have counted how many imps were in that game. Imagine what I could have learned? Now that would be interesting.

Joshua “Jammer” Smith

10.16.2023

Like what you’re reading? Buy me a coffee & support my Patreon. Please and thank you.